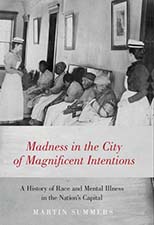

Book Prize Committee citation: Cheiron (The International Society for the History of Behavioral and Social Sciences) awards the 2021 Cheiron Book Prize to Martin Summers, (Professor of History and African and African Diaspora Studies, Boston College) for Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions: A History of Race and Mental Illness in the Nation’s Capital, (Oxford University Press, 2019).

In the 1840s, Charles Dickens characterized Washington D.C. as the “City of Magnificent Intentions,” both because of its stunning architecture and as yet relatively small population, as well as because the operations of slave traders within its borders challenged the American ideals of equality, freedom and democracy. When St Elizabeths Hospital opened in Washington D.C. in 1855 as a federally funded insane asylum for district residents and members of the US military, beliefs about race were central to the hospital’s location, design, and ongoing operation. Martin Summers’ engaging book examines the 132- year history of the hospital and its relationship with Washington D.C.’s African American community.

From its beginning, Saint Elizabeths Hospital was racially segregated and designed to prioritize the care of White patients over that of African American ones. The all-White hospital staff assumed that there were racial differences in psyche and that the White psyche was the norm. They viewed the Black psyche as deviant, inferior, primitive, child-like, and dangerous. In the antebellum period, low rates of insanity among African Americans were attributed to the “protection” slavery provided from the stresses of modern life. White psychiatrists then blamed the apparent increase in African American mental illness after the Civil War on emancipation. Summers highlights the contradictions in the characterizations of Black insanity. On the one hand, the most frequent diagnosis, especially early on was mania, and Black insanity was associated with depravity, violence and criminality. On the other hand, when overcrowding led to the necessity for housing White and Black patients together, they were sometimes housed with the White patients who were historically deemed idiots, or demented because Blacks were supposedly docile and less excitable to external stimuli and therefore less likely to object to being housed with these types of patients. When moral treatment was the dominant therapeutic approach, segregation of African Americans was considered necessary because it was believed that their excitable natures would threaten the serenity and therefore recovery of White patients No concerns were ever expressed about the effect White patients’ illness or behaviors might have on Black patients’ recovery. Work as therapy was also racialized. For Blacks it was intended to return them to life as laborers. For Whites (more often diagnosed as melancholic) to recover their spirits. The use of seclusion and restraints as well as later treatments such as hydrotherapy and dynamic psychotherapy also differed by race.

While acknowledging that many members of the hospital staff and administration were concerned about the mental health of their African American patients, Summers nevertheless identifies the racial assumptions that governed such treatment. At the same time, he highlights the agency of the African American community – patients’ attempts to control their therapeutic experiences and the ways the families, who viewed the hospital as an arm of the federal government, bravely asserted their rights as citizens to make demands of the hospital on behalf of their family member. Grounded in extensive archival sources and Summers’ expertise in African American history, Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions reminds us that the history of mental illness in America has only begun to grapple with the effect of race not just on diagnosis and treatment but also on the experience of the patients and their families

Members of the 2021 Cheiron Book Prize Committee: : Jennifer Bazar, Nancy Digdon, Kelli Vaughn-Johnson, and Katharine Milar (chair).